Our mission has always been to celebrate the transformative power of light. For over a decade, we’ve brought world-class lighting solutions to some of the most prestigious artworks and curatorial projects around the world. But our commitment goes beyond illumination—through our not-for-profit exhibition space, TM Gallery, we’ve cultivated a dynamic programme of contemporary art exhibitions, talks, and events. This space serves as a vital platform for mid-career artists, presented in collaboration with leading galleries and curators.

Our new Artist Spotlight series offers a glimpse into the minds of these artists—sharing the ideas, processes, and inspirations that shape their work.

First in the series is Nicole Wassall, whose upcoming exhibition at TM Gallery is titled ‘Retrospectively; Finding the Light’. In our conversation, Wassall explains the layered meaning behind the title—touching on themes of time, levity, spirituality, and hope, while also nodding to the fundamental role of expertly lit art.

Drawing on ancient philosophy, Wassall discusses how Lucretius—author of On the Nature of Things—informs her exploration of belief systems, mythology, and religion. She also shares how poetry acts as a form of visual sketching in her practice, capturing fleeting thoughts and shaping her creative direction.

With wit and warmth, Wassall reflects on joy, humour, and how these elements thread through her work—and how she unexpectedly became an ‘accidental feminist’.

With thanks to our programme curator, Hannah Payne, for this interview.

Nicole Wassall | ‘Retrospectively; Finding the Light’ opens on 11 September and runs until 7 October 2025 at TM Gallery, 7 Cubitt Street, London WC1X 0LN.

Your upcoming exhibition at the TM Gallery is entitled Retrospectively; Finding the Light. Tell us more about its meaning in the context of the exhibition?

You know when you’re talking to someone and there’s a magical moment, when they flick into their own world and get excited by an idea?

Well, that happened with Francesca (Fiumano Clase Gallery) when we were talking about the show. What excited her was that my work gains relevance over time, it was like she knew a secret and wanted me to have a retrospective so she could show everyone. Life experience and events on the world stage set her up to see new layers in the work. My response was naturally to grin childishly and exclaim, “I’ve never felt more seen!” When you make work like this, time is the test as to whether you have succeeded, and without the passing of time, you can’t fully get that.

The question then became how to articulate this in a way that’s relevant to that idea, the essence of my practice and the opportunity to have my work lit by the best in the business.

Hence, “Retrospectively; Finding the Light”. It captured a sense of time, light-heartedness, spirituality, hope, and literally the importance of lighting art well.

Image: Portrait of artist in front of artwork Mirror Mirror

Your work spans sculpture, gilded icons, mobiles, sound and even poetry. How do you decide which medium best suits a particular idea or theme?

The ideas take the lead and I’m left to chase after them like balloons on strings, sometimes I catch them other times they drift away.

It is in the processing of these ideas that I find the right medium. In terms of that process, generally it looks like intense research facilitated by the consumption of too much chocolate, as I filter out the noise around the punctums of life. This is followed by disrupted sleep, as my subconscious proposes different articulations in dreams, and with blurry eyes I scribble pictures and write notes in the middle of the night. Also, increasingly, poetry helps me develop ideas and to ruthlessly question my portfolio of thoughts, pulling them apart and putting them back together.

Usually this results in more research in the form of double-checking. Worth mentioning because of the moments of synchronicity, when it feels like the universe is telling me I’m on the right track. At this point, I will have a good idea of which medium(s) I’ll be using. However, even here the medium speaks to the piece and the work can change quite dramatically.

So, what I’m saying is the medium chooses itself as I process ideas, and it ends up feeling like I had little choice all along.

Image: Pope Joan

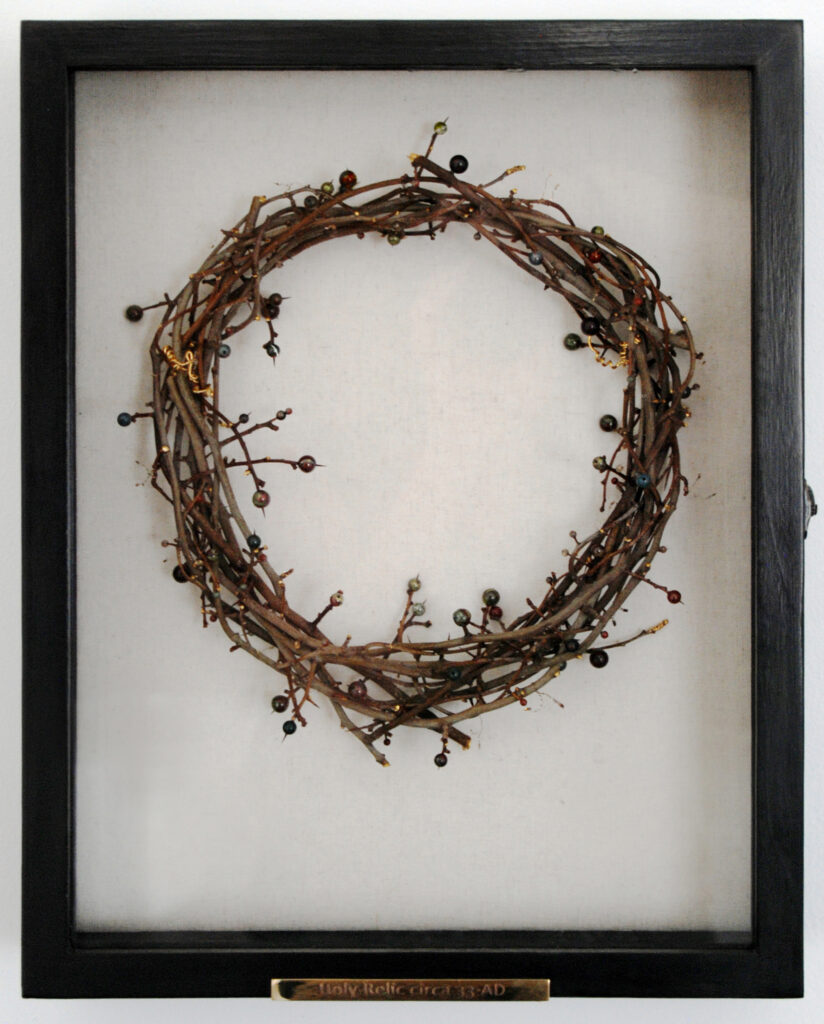

Several works in the show grapple with belief systems, mythology and religion – from “Holy Relic circa 33AD” to “Pope Joan, Patron Saint of Feminists”. What draws you to these subjects, and how do you approach them without being didactic?

Religion can be tricky, I find that interesting, and mythology has similar properties, whilst being less triggering. They provide familiar cross cultural and multi time-coded perspectives, imbued with cultural baggage. They can be used like magic spectacles, allowing us to look at contemporary culture in an ancient light, or maybe it’s an ancient culture being looked at in a contemporary light? Either way it is, as Roman philosopher and poet Lucretius wrote, “the nature of things”.

British philosopher John Gray argues the idea that “human progress” is a myth, not in terms of technology and science, et cetera, but in terms of human nature. He explains that lessons of ethics and politics are invariably lost over time and hence progress is a myth. I feel he is speaking to similar ideas; he’s just being more didactic.

But my motivations are different, I wish to awaken the critical mind, trigger curiosity and bypass confirmation bias. However, some people come to my pieces and, when their beliefs are challenged, they project ideas onto me and inevitably conclude “well she would say that wouldn’t she”.

Image: Holy Relic and symbols from I Wish the Hand Was Silver

You said you use poetry as a form of sketching. Can you share how this process works and how it shaped a piece like “Dove Moon”?

I don’t think in words, nor do I think in pictures; I think in thoughts. I can of course conjure images or a voice in my head, but they are not my default. This makes articulating ideas challenging; it is an interpretive process, like trying to find clarity in ancient text. So, whilst I’m translating elusive thoughts into meaningful ones, poetry becomes an interpreter and a way to sketch thoughts. It helps me extend ideas beyond the confines of a medium, and to sift through a clutter of ideas to find the essence.

With Dove Moon, it felt like a complicated idea, with different threads and many lines of scribbled poetry. Then I edited out everything that was ego and trying to be clever clogs, and kept what felt honest:

“Beauty in a sphere at night, peace the most beautiful light.”

In the context of what is going on in the world I stand by that. But all the lines that were erased, they are there too, the ghosts of words, never fully deleted. Poetry helps to interpret into both words and objects, while leaving space between the lines (or within the piece) for ideas to live.

And whilst it could seem as an add-on to my process, I think it’s more important than that. It’s shifting the balance from things I can imagine in images or words, to sharing thoughts more authentically. Using poetry like this may sound counterintuitive but it’s something my subconscious seems to want me to explore. Almost like my mind has a mind of its own and it’s taking over the process.

Image: Dove Moon

There’s a playful poignant thread running through your work – using humour to highlight contradictions in society and belief. Is humour a conscious tool in your artistic practice? E.g. “Flying Geisha Girl” and “The Point of No Return”.

There’s a lot of “embracing the inner child” in my practice, which is inherently playful and curious. So it’s less about using humour as a tool, and more about being natural and the joy of amusement.

If you take the “Flying Geisha Girl”, the situation could be seen as dire. The protagonist faces impending doom with humility and grace. Printed on white paper the kimono is hand painted white and her toenails a bright strong red. I was going through a phase of wearing Chanel Pirate No. 8 red toenail varnish. My friends were amused by the obvious similarity to the geisha girls’s toenails, despite my insistence that the red nails referenced the Japanese flag.

With “The Point of No Return”, if I’m honest, it was the inner child that was determined to make a piece with impossible balance. And it was with that childish enthusiasm that I marched into the kitchen show room, carefully selected a piece of marble, and asked if I could take it home. And so it goes on…

But at the same time, it is dangerous to explain a joke or humour, so forgive me if I’ve remained vague about specific examples of humour and focused on examples of how the attitude plays out.

Image: Flying Geisha Girl

In My Tree is Not Your Tree, the form of the tree carries both personal and symbolic weight. What ideas or tensions were you exploring through this work, particularly around questions of belief, authorship or contested meaning?

This question is hard to answer, but I will try. The piece came out of recovery from emotional abuse. It was me making sense of the internal mess that the bizarre behaviour of the abuser had left me with. It represents the unflinching determination to come out of that space and not end up like Dora Maar, a broken vessel whose brilliance was crushed. At the time I found there was work about the ‘damage’ and little about the ‘coming back’ from abuse.

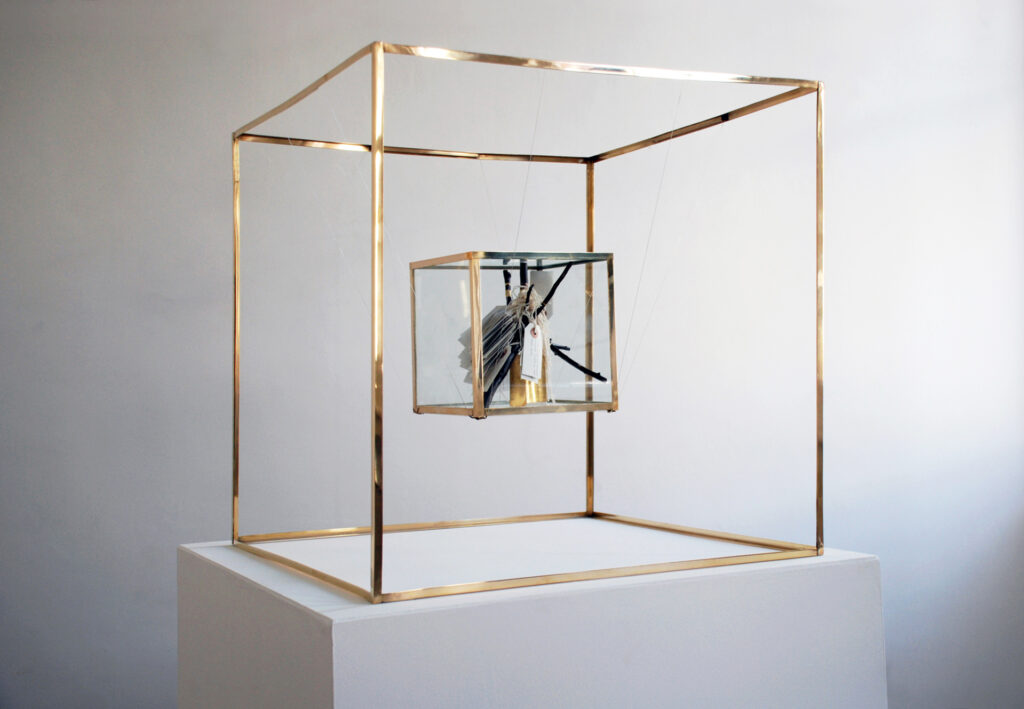

I found a rich vein of wisdom within the Japanese tradition of kintsugi and wabi-sabi, and solace in the idea that the broken vessel is repaired with gold and is considered more beautiful and valuable, because of the attitude towards the break.

When you are in the middle of it (abuse) you develop a kind of numbness when you stop noticing the little beautiful things: a bird singing on a branch, the quality of sunlight, a breeze and the delicate cherry blossom. A sign of recovery is when you notice these things again. The cherry branch in the centre of “My Tree” is the branch my little bird sat on, in that first moment of “coming back”. Hanging on the branch are thoughts typed with an antique typewriter. This inner box is sealed in glass. Some tags are water gilded with gold, at some level there is alchemy within the box; one tag floats upwards against gravity. Most of the thoughts on the paper tags are not hidden, they are just not visible; we cannot share all our thoughts, even if we wish to.

From a distance this inner box is floating within the delicate outer brass frame. On closer inspection, the inner box is suspended on gold wires. The balance is delicate. The outer brass frame creates the illusion of a glass barrier to the inner box.

In this way, the piece portrays the emotional boundaries (outer frame) we hope people will respect and the impossibility of revealing all that is inside (inner glass box of thoughts).

The title is a defiant permission to protect oneself and a necessary conclusion; My Tree is Not Your Tree.

Image: My Tree is Not Your Tree

Your piece Equality uses a metronome to evoke the ongoing tension between balance and progress. Can you talk us through the thinking behind this work, and how you hope viewers will experience it?

The piece should be wound up and the weight extended to its outer limit, so the arm swings uncomfortably slowly, whilst taking care not to over wind the mechanical mechanism, because that does more harm than good. The clicking disappears surprisingly easily into background noise. The viewer sees their reflection in the golden mirror surface, embodying the precious nature of the material and time. The title, Equality, unlocks the significance of these elements.

The piece is experienced differently during a noisy private view, where the sound disappears into the background, and a quiet personal tour, where it can be distracting and annoying. Both experiences are part of the piece. It is a context dependent piece, what is happening in the gallery, what experience the viewer brings to it and so on. Some people will see it as a piece about feminism, others racism et cetera… the point is, it is about Equality, and how you experience that depends on your context.

Image: Equality

Looking back at the past decade of your practice, what has surprised you most about how your work has evolved or been interpreted?

The biggest surprise was the rise of feminism in my work. That was the furthest thing from my mind when I started, it didn’t feel that relevant. There were more important things to be covering, you know, like Game Theory and the silencing of political voices.

A little naive I suppose. I had a career in consultancy and whilst it was an issue, determination and capability allowed me to thrive. I assumed this would be enough in the art world too, but just like the metronome clicks painfully slowly, so does equality in the art world.

But there is a liberation in that, or at least I have found one. We are freer to experiment, make mistakes, write our own rule book and do things our own way. The traditional model does not work for women artists, we have to do it differently, what a wonderful training ground to make art. So I am free to push boundaries and then sit back and have a gin and tonic, with Francesca and Pope Joan.